I was once sitting with my dad googling how far different things in the solar system are from Earth. He was looking for exact numbers and was very obviously investing more with each new figure I shouted out. I was excited. Moon? An average of 238,855 miles (384,400 kilometers) away. The James Webb Space Telescope? Throw it up to about a million miles (1,609,344 km) away. Sun? 93 million miles (149,668,992 km) away. Neptune? 2.8 billion miles (4.5 billion km) away. “Well, wait until you hear about Voyager 1,” I finally said, assuming he was aware of what was coming. He wasn’t.

“NASA’s Voyager 1 interstellar probe isn’t actually even in the solar system anymore,” I announced. “No, it’s more than 15 billion miles (24 billion km) from us – and even further away as we speak.” I don’t remember his answer, but I do remember the look of utter disbelief. Questions immediately arose as to how this was even physically possible. There were confused laughs, different ways to say “wow” and mostly an infectious sense of wonder. And just like that, a new Voyager 1 fan was born.

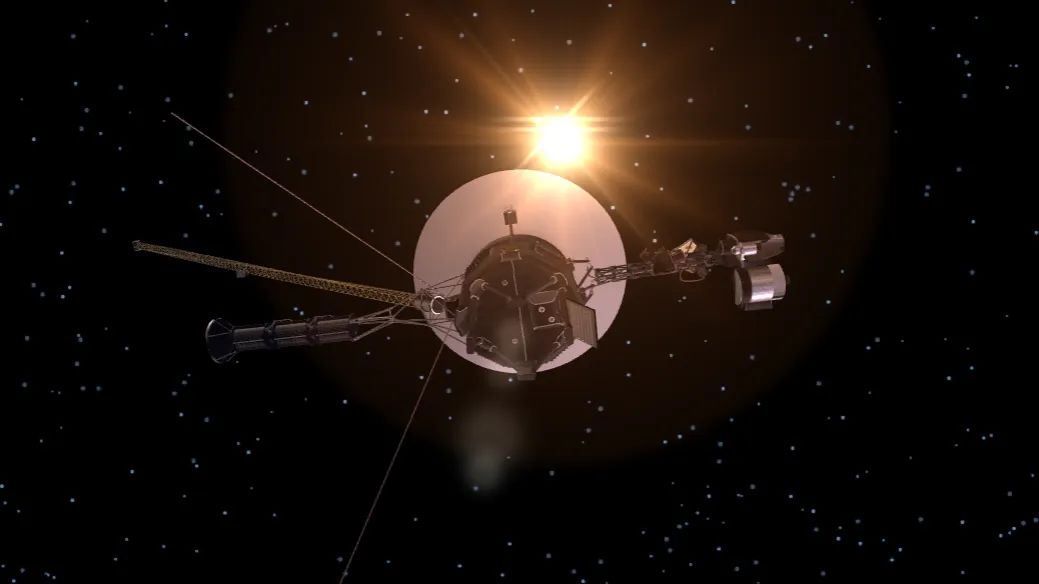

It’s easy to see why Voyager 1 is among the most popular robotic space explorers we have—and so it’s easy to understand why so many people felt heartbroken when Voyager 1 stopped talking to us a few months ago.

Related: After months of sending gibberish to NASA, Voyager 1 is finally making sense again

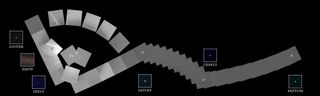

For reasons unknown at the time, the spacecraft began sending back gibberish instead of the neatly ordered and data-rich ones and zeroes it had been providing since its launch in 1977. It was this classical computer language that allowed Voyager 1 to converse with its creators while earned the title of “most distant human object”. It’s how the spacecraft delivered crucial insights that led to the discovery of new Jovian moons, and thanks to this kind of binary podcast, scientists incredibly identified a new ring of Saturn and created the first and only “family portrait” of the solar system. This code is essentially essential to Voyager 1’s very being.

Additionally, to top it all off, it turns out that the problem behind the glitch is related to the craft’s flight data system, which is literally the system that transmits information about Voyager 1’s health so that scientists can fix any issues that arise. Problems like this. Furthermore, due to the vast distance of the spacecraft from its operators on Earth, it takes about 22.5 hours for the transmission to reach the spacecraft and then 22.5 hours for the transmission to be received back. Unfortunately, things didn’t look good for a while – about five months to be exact.

But then, on April 20, Voyager 1 finally called home with readable 0s and readable 1s.

“The team met early over the weekend to see if the telemetry would come back,” Voyager flight team member Bob Rasmussen told Space.com. “It was nice to have everyone gathered in one place like this to share the moment when we knew our efforts were successful. We cheered both for the intrepid spacecraft and for the friend who made its recovery possible.”

AND then, On May 22, Voyager scientists released a welcome announcement that the spacecraft had successfully resumed transmission of science data from two of its four instruments, the Plasma Wave Subsystem and the Magnetometer. They are now working to bring two more, the Cosmic Ray Subsystem and the Low Energy Charged Particle Instrument, back online as well. Although there are technically six other instruments aboard Voyager, they have been out of service for some time.

Return

Rasmussen was actually a member of the Voyager team in the 1970s, working on the project as a computer engineer before going on other missions, including Cassini, which launched the spacecraft that taught us almost everything we know about Saturn today. However, he returned to Voyager in 2022 due to a separate mission dilemma – and has remained with the team ever since.

“There are many original people who were there when Voyager launched, or even earlier, who were part of the flight team as well as the science team,” Linda Spilker, a planetary scientist at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory who also worked on the Voyager mission, told Space. com on the This Week from Space podcast on TWiT. “It’s a real tribute to Voyager — to the longevity of not just the spacecraft, but the people on the team.”

In order to get Voyager 1 back online, in a more cinematic way, the team devised a complex solution that caused the FDS to send a copy of its memory back to Earth. As part of this memory read, the operators were able to discover the core of the problem—corrupted code involving a single chip—which was then fixed by another (honestly, super interesting) code modification process. The day Voyager 1 finally spoke again, “you could have heard a pin drop in the room,” Spilker said. “It was very quiet. Everyone is looking at the screen, waiting and watching.”

Of course, Spilker also brought some peanuts for the team to munch on—but not just any peanuts. Lucky peanuts.

It’s a long-standing tradition at JPL to hold peanut parties before major mission events like launches, milestones and, well, the possible resurrection of Voyager 1. It started in the 1960s when the agency was trying to launch the Ranger 7 mission, which was intended to take pictures and collect data about the surface of the moon. Guardians 1 through 6 failed, so Guardian 7 was a big deal. As such, mission trajectory engineer Dick Wallace brought the team plenty of peanuts to munch on and rest. The Ranger 7 was certainly a success, and as Wallace once said, “the rest is history.”

Voyager 1 needed some positive snacks.

“It’s been five months since we had any information,” Spilker explained. So in this room of silence except for the sounds of eating peanuts, the Voyager 1 operators sat at their respective system screens and waited.

“All of a sudden it started filling up — the data,” Spilker said. That’s when the programmers who had been staring at those screens in anticipation jumped out of their seats and started cheering: “I think they were the happiest people in the room and there was just a sense of joy that we had Voyager 1 back. .”

Ultimately, Rasmussen says, the team was able to conclude that the failure was likely due to a combination of aging and radiation damage from energetic particles in space bombarding the craft. It’s also why he believes it wouldn’t be too surprising if a similar failure occurs in the future, as Voyager 1 is still traveling beyond the far reaches of our stellar neighborhood, as is its twin spacecraft, Voyager 2.

To be sure, the spacecraft isn’t fully repaired yet – but it’s nice to know things are finally looking up, especially with recent reports that some of its science instruments are back on track. And Rasmussen, at least, assures that nothing the team has learned so far has been alarming. “We believe we have a good understanding of the problem,” he said, “and we remain optimistic that everything will return to normal – but we also expect it won’t be the last.”

In fact, Rasmussen explains, the Voyager 1 operators became optimistic about the situation as soon as the root cause of the malfunction was determined with certainty. He also emphasizes that the team’s morale has never been low. “We knew from circumstantial evidence that we had a spacecraft that was mostly healthy,” he said. “We didn’t think about saying goodbye.”

“Rather,” he continued, “we wanted to push for a solution as quickly as possible so that other matters on board that have been neglected for months can be addressed. We are now moving steadily toward that goal.”

The future of Voyager’s journey

It cannot be ignored that over the past few months there has been an air of anxiety and fear in the public sphere that Voyager 1 is slowly moving towards sending us its final 0 and final 1. Headlines all over the internet, including one written by me, have a clear negative weight. I think it’s because even if Voyager 2 could technically carry the interstellar torch after Voyager 1, the prospect of losing Voyager 1 felt like the prospect of losing a piece of history.

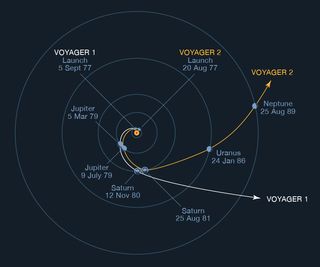

“We’ve crossed this boundary called the heliopause,” Spilker explained of the Voyagers. “Voyager 1 crossed this threshold in 2012; Voyager 2 crossed it in 2018 – and since then it has been the first spacecraft ever to make direct measurements of the interstellar medium.” This medium basically refers to the material that fills the space between stars. In this case, it’s the space between other stars and our sun, which, although we don’t always think of it as one, is just another star in the universe. A drop in the cosmic ocean.

“JPL started building the two Voyager spacecraft in 1972,” Spilker explained. “For context, this was just three years after we had the first human walk on the moon – and the reason we started so early is because we had this rare planetary alignment that happens once every 176 years.” It is this alignment that could promise spacecraft checkpoints across the solar system, including Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus and Neptune. These checkpoints were especially important to the Voyagers. Along with planetary visits comes gravity assist, and gravity assists can help eject things inside the solar system—and now, we know, beyond.

As the first man-made object to leave the solar system, a holdover from the early American space program, and a testament to how robust even decades-old technology can be, Voyager 1 created the kind of legacy usually reserved for remarkable things lost. on time.

“Our scientists are eager to see what they missed,” Rasmussen noted. “Everyone on the team is motivated by their commitment to this unique and important project. That’s where the real pressure comes from.”

Still, in terms of energy, the team’s approach was clinical and determined.

“No one was ever particularly excited or depressed,” he said. “We’re confident we can return to normal operations soon, but we also know we’re dealing with an aging spacecraft that will have problems again in the future. That’s just a fact of life on this mission, so it’s not worth to upset it.”

However, I think it’s always a pleasure for the Voyager 1 engineers to remember that this robotic explorer is keeping curious minds busy around the world. (Now including my father’s mind, thanks to me and Google.)

As Rasmussen says, “It’s amazing to know how much the world appreciates this mission.”

Originally published on Space.com.